Despite the increasing popularity of body-worn cameras, the technology has its detractors. For example, this month Big Brother Watch, a British civil liberties and privacy organisation, is raising new questions about the effectiveness of body-worn cameras. Specifically, Big Brother Watch found that 32 of the 45 police forces that have adopted body-cams in the United Kingdom were “unable to say” how often the footage was used in courts. To be clear, being “unable to say” doesn’t equate to the cameras not being useful, and using video as evidence in court is just one of the possible ways the cameras could be beneficial.

Even so, point taken. Adoption of the body-worn cameras continues full speed ahead despite lack of empirical evidence of their effectiveness. Studies in the United States and Canada on the effectiveness of the cameras have also often been inconclusive. Big Brother Watch warns: “The value of technology must be proven and not just assumed. It is not enough to tell the public they are essential policing tools if the benefits cannot be shown.” In addition to seeking more data on camera effectiveness, the organisation urges police forces to publish regular “transparency reports” to show how body worn cameras are used in day-to-day policing. Cameras should also have a screen to display when citizens are being recorded.

Does video surveillance prevent crime?

In some instances, police forces have embraced the cameras on the assertion that the police and/or the public believe they are beneficial. But believing something doesn’t make it true.

Body-worn cameras are not the first video systems whose effectiveness has been questioned. There have also been repeated challenges over the years to the effectiveness of video or CCTV cameras in preventing crime. For example, one report in Chicago placed the number of crimes solved by video evidence between the years 2006 and 2013 at 4,500. Not bad, except when you consider there were more than a million incidents during the time period, and surveillance cameras helped solve less than 0.5 percent of them. Looking at it another way, the numbers work out to one crime solved for every five cameras; i.e., the average camera never solves a crime -and then there were the British Home Office studies in 2002 and 2005 that questioned the impact of CCTV cameras on crime.

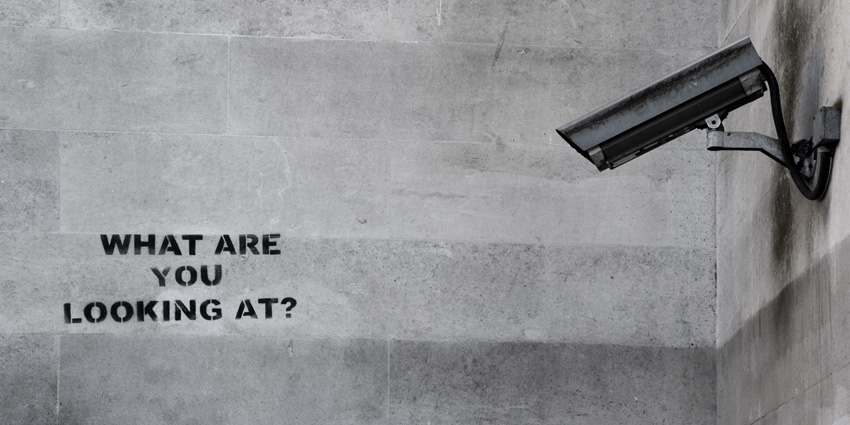

|

| [Jeremy Reddington / Shutterstock.com] British Home Office studies have questioned the impact of CCTV cameras on crime |

Quantifiable benefits of security products

Again, however, solving crime is only one aspect of the benefits of video. There is also a “halo effect” when cameras are installed. That is, the areas where cameras are deployed tend to be more secure, even outside the immediate view of cameras. There is a diffusion of crime prevention benefits to surrounding areas.

Questioning the effectiveness of body-worn cameras, CCTV or any other technology, is a necessary exercise. Real answers may be hard to come by, but we shouldn’t be discouraged in making the effort. The technology capabilities of our industry’s products should be able to withstand scrutiny and, in the end, provide verifiable and quantifiable benefits.

Public scrutiny of security systems

Public scrutiny is an important aspect of technology implementation, especially in the public sector. For private companies, there is another, even more potent force at work that focuses attention on the effectiveness of technology – the bottom line. Spending money on video (or other technologies) is viewed unforgivingly through a lens of return on investment (ROI) by managers and accountants of customer companies. Fortunately, in this environment, video systems more than justify their existence every day.

It only takes avoidance of a single multi-million-dollar personal injury lawsuit to cost-justify a whole system of video cameras. The impact of video to deter shoplifting or other crimes, and the resulting extra value to an enterprise, is sufficiently demonstrated every day.

We as an industry should welcome any questions about the effectiveness of our products. Their value can speak for itself, and can stand up to any questioning or research projects. If it doesn’t, then we must be willing to let the chips fall where they may.