|

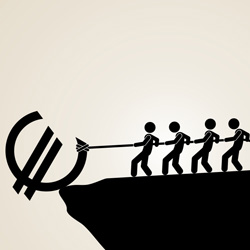

With elections due later this year in the UK, Spain and Switzerland, attitudes to the prevailing political landscape of austerity are changing rapidly. Are physical security budgets in the public sector ever protected from cuts, and what is the outlook for our industry?

Consider the landscape: A left-leaning party has come to power in Greece on an anti-austerity platform and with the stated intention of halving the country’s €315bn debts. Angela Merkel, the German Chancellor, has rejected the proposal out of hand saying that creditors have already proved generous in their concessions. Meanwhile, the hard-left Podemos party in Spain has aligned itself with the Greek government and organised marches in which 100,000 people packed the main squares of Madrid. Opinion polls suggest that Podemos could sweep to victory at the December election.

It might be counter-intuitive, but any industry observer will tell you that when a recession leads to public protests and social unrest, governments usually reduce their spending on policing and camera surveillance as part of general budgetary consolidation. Our sector doesn’t enjoy immunity, an inconvenient truth illustrated in the UK when, during its second year, the present Coalition saw riots in London, Liverpool and the West Midlands but promptly reduced annual spending on public order and safety by £3bn. At a more micro level, while total UK public expenditure in the first two years of the Conservative-Liberal Democrat alliance fell by only 1.4 percent, police numbers in England and Wales dropped by 7 percent.

The recent terrorist attacks in France prompted Prime Minister Manuel Valls to announce the hiring of 2,680 extra security personnel and purchase of additional security equipment to the value of €425m. He has been understandably reserved about specifics, but it’s known that the physical (as opposed to cyber) elements of this budget will be spent in part on airport screening as well as bullet-proof vests, helmet-mounted cameras and new vehicles for police. The spending is in addition to previously planned police hirings.

|

| CCTV remains a technology that is used primarily for evidence gathering, deterrence and communicating information |

ISIS has promised attacks on European cities (a plot to storm police stations in Belgium was foiled at the 11th hour in January), and increased vigilance at border controls is unlikely to provide adequate protection. Researchers based at King’s College, London University, estimate that 1,900 European citizens travelled to Syria last year with the intention of waging jihad, and it’s a logical supposition that similar numbers of disaffected people with potential for radicalisation remain in Europe.

The whole security landscape changed with the 1983 Beirut barracks suicide bombing. Despite rapid advances in video analytics, CCTV remains a technology that is used primarily for evidence gathering, deterrence and communicating information (often very effectively) once a major incident has begun. The jihadist suicide mindset, by definition, reduces the importance of evidence gathering at a crime scene and negates surveillance as a deterrent. Only rarely do cameras alert authorities to a potential threat.

But at the same time, advances in CCTV are assisting police significantly with mainstream public order offences. In a development that has bucked the trend of budget austerity, UK constabularies are placing large orders for body-worn cameras, and 16,000 will be in use by the Metropolitan Police this time next year. The cameras are becoming increasingly flexible, and most models can be transferred from an officer’s clothing to a tactical helmet at will.

Security manufacturers are proving responsive with their business models as the scramble for limited budgets intensifies, and forward-thinking R&D departments have exploited cloud computing to offer video surveillance and access control “as a service.” |

Security manufacturers are proving responsive with their business models as the scramble for limited budgets intensifies, and forward-thinking R&D departments have exploited cloud computing to offer video surveillance and access control “as a service.” This is an almost Darwinian correlation between adaptability and success in an environment of extreme competition.

Few of the correlations I expected as I researched the effect of economic austerity on crime figures have proved true. Mass unemployment means many people with time on their hands and an economic motivation to steal from shops. Conversely, a buoyant labour market will surely see a reduction in retail theft? And yet unemployment in the UK is currently at six percent – its lowest since the banking collapses of 2008 – but retail crime rose by 18 percent in 2014 compared with the previous year. Real-life conditions outside the statistical model of the economist remain harsh, and private sector retailers are investing in advanced security to combat “shrinkage” with megapixel cameras and devices to detect career thieves who equip themselves with de-tagging devices and foil-lined shopping bags.

In the government sector, austerity is currently reflected in “make do and mend” attitudes from senior public servants controlling budgets. Again, our industry is proving responsive with an upsurge in hybrid surveillance systems using both IP cameras and analogue devices deemed still fit for purpose. It’s a graduated model that appeals to accountants who are trying to consolidate spending even if they don’t understand the technology.

I would be interested in hearing about the in-the-field experiences of installers of hybrid systems. Do they perform consistently at anything more than 12.5 fps, and how effective is this rate for evidentiary purposes?